Welcome to Ceramic Review

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

Ceramic Review Issue 334

July/August 2025

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

July/August 2025

A major exhibition, The Journey of Things, brings together ceramic artist Magdalene Odundo’s pots with a diverse selection of objects made over the last 5000 years. Ahead of its opening, CR’s Isabella Smith spoke to Odundo and the Hepworth Wakefield’s curator Andrew Bonacina to learn more about the show. This article is from CR 296 (March/April 2019).

Portrait of Magdalene Odundo. Photo by Robert Walker

The ceramic artist Magdalene Odundo is firmly in the spotlight this year, as Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things opens at Hepworth Wakefield in February then travels to The Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, in the autumn. Reflecting Odundo’s status as one of our most eminent ceramic artists – in 2008, she was awarded an OBE for services to art – the exhibition offers more than a conventional retrospective.

While bringing together over 50 of her own works from the 1970s onwards, it also offers an in-depth look at the objects that have informed her artistic development. ‘Research of global cultures, histories and making traditions has played an important role within my career from the beginning,’ says Odundo. ‘I’m looking forward to sharing some of these insights with visitors.’

The objects the Kenyan-born British artist has selected for display are richly diverse – from Ghanaian ritual figures to Edgar Degas’ famous sculpture Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1880–81) – yet they all make sense in the context of Odundo’s practice.

‘There will be ceramic works by great teachers such as Michael Cardew and Henry Hammond, both of whom played an important part in encouraging my early career,’ says Odundo. ‘Other objects, such as a tiny, ancient Cypriot bowl that was owned by Barbara Hepworth, reveal the incredible versatility of clay. They opened my eyes to the possibilities of what can be achieved using this simple material. There are so many wonderful objects in this exhibition, which have all had an impact in one way or another, that it is difficult to single any out,’ she adds.

Research of global cultures, histories and making traditions has played an important role within my career from the beginning

Unsurprisingly perhaps given its unique diversity of influence, the pots Odundo has created over the last half century are instantly recognisable as hers. They are large, sometimes asymmetrical vessels, with outlines that often recall the human body. Their finishes are equally distinctive: a lustrous terracotta orange, deep black, or occasionally a smoke-like variation between the two.

Magdalene Odundo, Untitled, 1985, burnished and oxidised terracotta. Photo courtesy Phillips

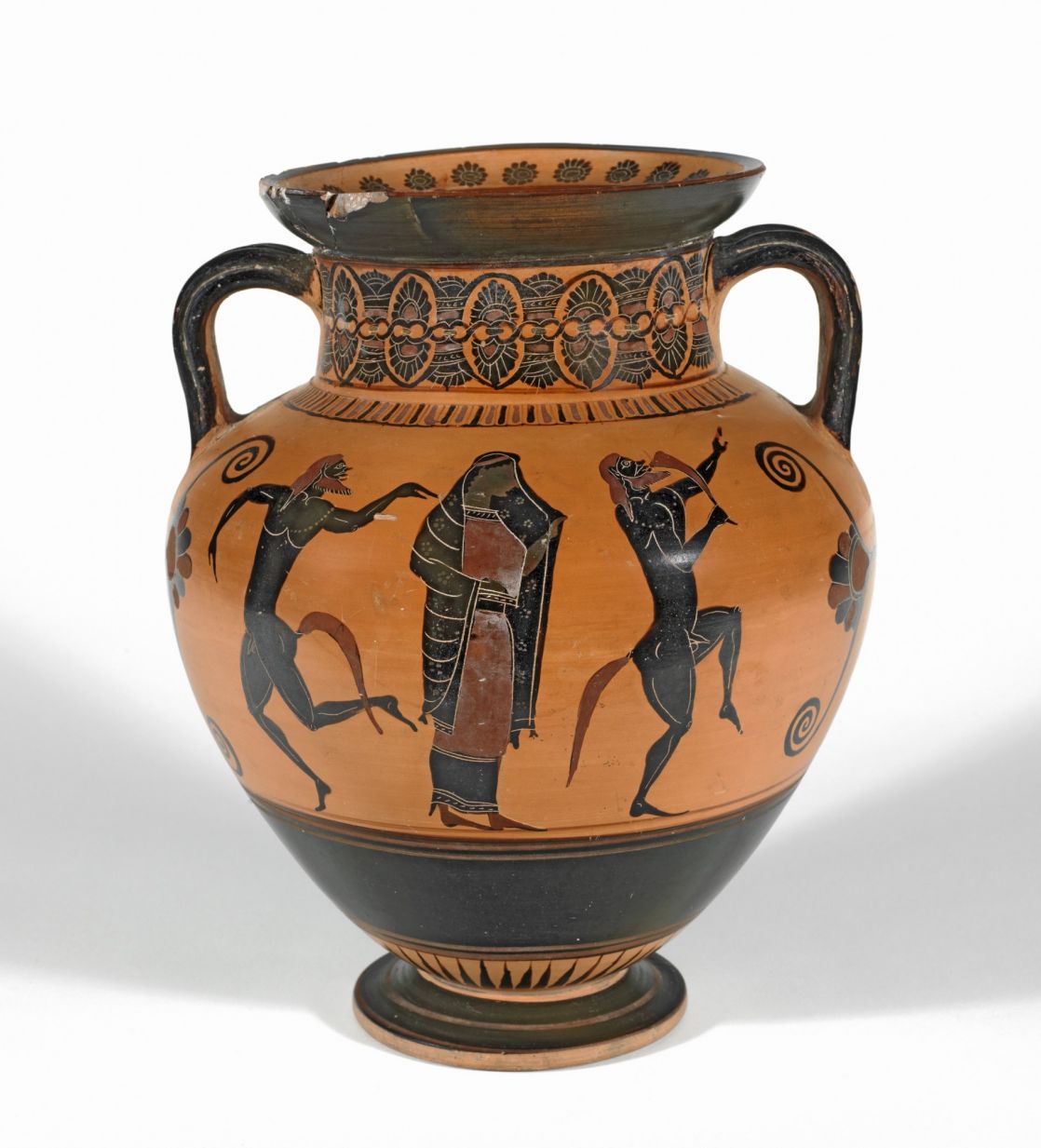

Black-figured neck-amphora with Ariadne between dancing satyrs, Greece, c.550–540BC. Photo © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Odundo handbuilds her pots using ancient techniques. A lump of clay is pinched upwards into a full, rounded body, to which she adds the coils that will form the shoulder, neck and mouth. They are burnished while leatherhard, sprayed with terra sigillata, then burnished again. Using a gas kiln, the orange pots are fired once in an oxidising atmosphere. The black are fired like the orange first, then placed in a saggar and reduction fired. These may be fired up to five times to attain the right density of blackness.

MULTICULTURAL MAKING

Odundo was born in Nairobi, Kenya, and attended schools in both India and her homeland. Despite this, she was not particularly aware of local pottery traditions. It was only after moving to Cambridge, England, in 1971 to study on an art foundation course that she began to consider ceramics more seriously – in particular, anthropological and ethnographic artefacts in the Fitzwilliam Museum caught her eye.

She went on to study ceramics at West Surrey College of Art and Design in Farnham (today the University for the Creative Arts, where Odundo is now Chancellor). Michael Cardew recommended that she travel to the centre he had established in Abuja, Nigeria, where she could learn traditional techniques from local potters. It was here that she worked alongside the famous Gwari handbuilder, Ladi Kwali. She also learned from ceramics encountered back in Kenya, and visited San Ildefonso Pueblo in New Mexico, USA, to study the making of blackware vessels.

On Odundo’s return to England she studied at the Royal College of Art, where she synthesised her eclectic interests into her own inimitable style. These influences are only some of the inspirations behind Odundo’s work, which is expansive in its multiculturalism. ‘One of the oldest ceramic pieces we are displaying is an ancient Egyptian terracotta vase dating from 3000BC,’ notes chief curator Andrew Bonacina. ‘It is astonishing that it survives at all, but its simple aesthetic could lead it to be mistaken for something far more modern. We also have a Cypriot earthenware juglet from 1750–1650BC that is decorated with small nodules, not unlike some of Odundo’s own works with their distinctive silhouettes.’

CLAY BODIES

It is, by this point, a cliché to point out the parallels between ceramic vessels and the human form. Nevertheless, when it comes to understanding Odundo’s work, the cliché needs repeating. Many items in The Journey of Things draw directly from the figure: from Cycladic figurines, and Greek amphorae painted with black-figured dancers, to Barbara Hepworth’s rosewood Kneeling Figure (1932).

Magdalene Odundo, Untitled, 1989. © Magdalene Odundo. Photo by Bill Dewey

Barbara Hepworth, Kneeling Figure, 1932, rosewood. Photo © Bowness

I do not see the difference between a figurative sculpture and a figurative vessel

Though less literal, Odundo’s pots are distinctly anthropomorphic. Raised bone-like areas recall vertebrae, an Adam’s apple, or a belly button; dramatic flared rims conjure the outline of a jaw or the incline of a head. It’s not unusual for the necks of these pots to recall, well, necks, blurring the boundaries between abstraction and figuration. Odundo is firm on this aspect of her work, stating: ‘I do not see the difference between a figurative sculpture and a figurative vessel.’ Perhaps unsurprisingly, she is committed to the practice of life drawing, believing that it ‘gives humanity’ to her pieces.

‘The exhibition will be a unique opportunity to see a broad range of Odundo’s work from the 1970s to the present reunited in one place,’ says Bonacina. ‘Many pieces have been purchased by private collectors from around the world who have generously agreed to loan them for this exhibition. Magdalene’s personal selection of objects has been crucial, as has her ability to work closely with architect Farshid Moussavi who has conceived how we can present so many different types of objects in a cohesive design.’

When asked what she would like people to take from the show, Odundo answers with enthusiasm. ‘I want visitors to be amazed at the power of clay, its history and artistic universality. Its simplicity as the ultimate material to work with is magical – this humble and very natural human material can be moulded and formed into anything.’ She adds: ‘It is plastic and pliable and has the capacity to transform from clay to ceramics in endless permutations!’

Magdalene Odundo: The Journey of Things is at the Hepworth Wakefield from 16 February to 2 June; hepworthwakefield.org

This article is taken from Ceramic Review issue 296 (March/April 2019). For more, subscribe below.