Welcome to Ceramic Review

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

Ceramic Review Issue 334

July/August 2025

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

July/August 2025

Through form and surface, Mike Stumbras investigates the influences and experiences behind Peter Pincus’ elegant porcelain vessels

work by Peter Pincus; courtesy of the artist

Peter Pincus’ slip-cast porcelain vessels are renowned for their exquisite investigations of ceramic culture. Energetic in form and assertive in the use of colour, his work emerges from the kiln self-aware of its connections to contemporary practices, historical production, and their status as culture-transmitting objects. He pairs elegant and occasionally monolithic forms with surfaces that betray a long-term study of colour theory, modular design and international studio ceramic practices. Pincus self-identifies as a potter. He arms himself with a technical proficiency that both celebrates and confronts trends in American studio ceramics and historical mould-making techniques.

FUNCTIONAl FRAGILITY

Pincus’ surfaces and forms work together to carve out a sense of space marked by an uncanny familiarity and a notable formal friction. His vessels are constructed from complex moulds that can contain up to 200 separate plaster components and a porcelain that is often fired repeatedly at a range of different temperatures to allow for the use of various surface techniques.

Viewing the work in person is a lovely experience: buttery swathes of fine-coloured porcelain punctuated with festoons of gold lustre beg for a caress, while exaggerated formal elements and dynamic colour contrasts allude to the numerous tensions between function and fragility. Taking inspiration from painting, sculpture and fashion, Pincus approaches his work with a genuine curiosity towards documenting and understanding how handmade ceramic containers relate to humanity within our place in time.

Pincus was first exposed to ceramics in 1998 in Rochester, New York, where he took a course to fulfil a credit obligation in his junior year of high school. Entering the classroom with low expectations, he saw a student throwing on the potter’s wheel and was captivated. ‘I knew instantly that was it,’ he explains. ‘That was what I needed.’ He quickly became dedicated to the practice of throwing, soliciting help from his teachers and peers and eventually finding

a way to get his own wheel. Pincus describes how exposure to clay in the latter part of his education changed his thinking about his trajectory in ceramics: ‘Prior to that experience, I had no interest in college or anything of that nature. It all grew out of that one class.’

At the urging of a friend, he pursued a Bachelors of Fine Arts at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University. Close in proximity to Rochester, Alfred University boasts one of the top ceramic art programmes in the US. During his time there, Pincus began experimenting with mould-making techniques, beginning a serious and ongoing study of slip-casted forms modelled from wheel-thrown components.

His perseverance and drive led him to continue his studies and he took the time to refine his craft while serving as a resident artist at the Mendocino Art Center in California, before receiving his Masters in Fine Art from the College of Ceramics at Alfred. He has since completed a residency at the Archie Bray Foundation in Helena, taught at Haystack School Mountain School of Craft and worked as a Studio Manager and Resident Artist Coordinator at the Genesee Center for Arts and Education in Rochester. Despite an initial passion for studio practice, while working, Pincus also hit his stride as a teacher and developed an understanding of the intersection between scholarship, studio practice, service and pedagogy.

work by Peter Pincus; courtesy of the artist

work by Peter Pincus; courtesy of the artist

In autumn 2014, he joined the faculty at the School for American Crafts at Rochester Institute of Technology as Assistant Professor of Art, where he teaches today. ‘I think it is a very complex place. It is full of ever-evolving individuals who generationally change quite a bit,’ Pincus says. ‘The people we are, are not the people we teach. It is a tough pill to swallow sometimes when, even in the last 15 years, you see such changes among students in cognition, in apathy and connectivity.’ Pincus places an emphasis on trying to meet students where they are and understanding them as they change.

INFLUENTIAL IDEAS

Pincus’ creative practice is driven by inquiry and is syncretic in its combination of diverse research interests. He is careful when he selects his words about his influences: ‘There is a big difference between being influenced by and being in conversation with an object. As an artist and educator, I am eager to acknowledge those who have elevated my thinking through their work.’

His process begins with an exploration of form and colour in relation to specific artistic research. He explains that his studio practice has a close linkage with his goals as a teacher. ‘At the heart of all of this, I am using my work to start to have a better understanding, so that I can better articulate ideas to my students,’ he says. His two recent exhibitions investigate his ideas about influence and appropriation in order to embrace the complexity involved in the visual study of history. ‘The idea of trying to build the conversation – trying to relate it to other things while also trying to respect what it is as much as you can – is important to me,’ he explains.

The 2018 exhibition Peter Pincus: Channelling Josiah Wedgwood offered an interpretation of the Dwight and Lucille Beeson Wedgwood Collection at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Birmingham, Alabama. Pincus presented a collection of vases that acknowledge their connections to the ceramics industry in 18th-century England, something he refers to as ‘concept poaching’: ‘You have appropriation at a cultural or cross-cultural level. And then, in the same period of time, you have appropriation at an inter-cultural level,’ he explains. ‘This is so amazingly apparent around this period of time. However, it is so subtle now, because of everything we are going through and how much has happened since then.’

work by Peter Pincus; courtesy of the artist

work by Peter Pincus; courtesy of Ferrin Contemporary

A series of slip-cast Calyx Kraters that take their name from ancient Greek mixing vessels are also included in the exhibition. These forms have been repeated and altered uncountable times throughout history and can be directly seen in examples from Wedgwood’s oeuvre. Pincus’ pieces contemporise the inspiration with streamlined forms, dynamic applied slip colours and modernised construction processes. ‘Part of the appeal is tracing an object from antiquity to present day, through Wedgwood and then through current computer-aided design technologies and other contemporary methods,’ explains Pincus. The role that these pots play is more rooted in iconography and paradigm than in function. They suggest an interpretation that ceramic vessels may exist as part of a continuum of influences rather than as distinct entities.

Pincus has explored the myriad ways his ceramics have been affected by Wedgwood’s legacy: ‘Even just making two or three objects for the show, to put forward a group of vessels that are connected to this Wedgwood research, and then populate the show with objects that are somewhat more tangentially related was very complicated. It represents this need to better understand imitation, appropriation, and how all of that works.’

CONNECTING THE DOTS

Building on Channelling Josiah Wedgwood, the 2020 exhibition Art in the Age of Influence: Peter Pincus | Sol LeWitt at Ferrin Contemporary in North Adams, Massachusetts, examined how Pincus digests and responds to visual and conceptual influences. Gallery director Leslie Ferrin remarked how, ‘like LeWitt, Pincus often begins a new series using a premise to explore various possibilities of form and colour within a shared framework.’ Comparing this to his Wedgwood work Pincus notes: ‘There is a slight difference about influence and how it works, with one exhibition being a little more passive in nature, and one being more active. The LeWitt study was about subconsciousness, about flipping through the internet and seeing things all day, every day, and then trying to connect the dots with what it actually means or what matters to you.’

The centrepiece of the exhibition was a series of 15 large-scale monumental columns with a colour spectrum across the surface that, when viewed as a unit, creates a painting-like landscape that relates directly to LeWitt’s wall drawing Losing #422. ‘Regarding Losing #422, I feel strongly that it starts by trying to take some ownership over the nature of how someone informs your decisions; and to accept and acknowledge that,’ Pincus explains.

work by Peter Pincus; courtesy of the artist

The exhibition required an extensive and technical use and study of colour. ‘It was a very intuitive process that was built around the idea that we have a limited palette, based on this limited material,’ Pincus describes. ‘I was looking for interesting ways to combine the colours that we have. In the case of LeWitt’s Losing #422, I took that image and placed it on my work so that it would reflect LeWitt’s code, which in that particular object is grey, yellow, red, blue.’

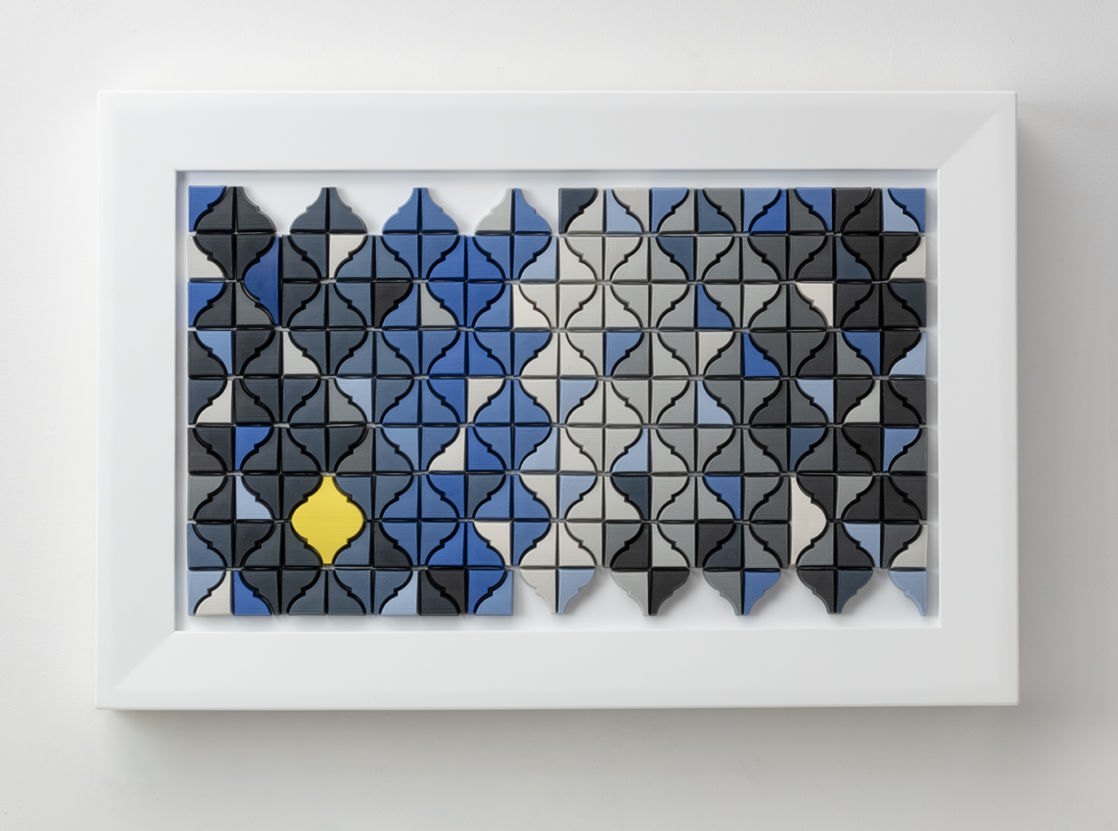

The other pieces in the exhibition, including First Start, a tessellating tile composition, and expertly crafted porcelain vessels, celebrate a continuity and a dissonance in form and colour that emulates and celebrates influences from LeWitt’s conceptions, as Pincus explains: ‘The exhibition was an opportunity to celebrate LeWitt’s approach to making as a foundation from which I could challenge myself to see new things and to grow.’

For more details visit peterpincus.com

work by Peter Pincus; courtesy of the artist