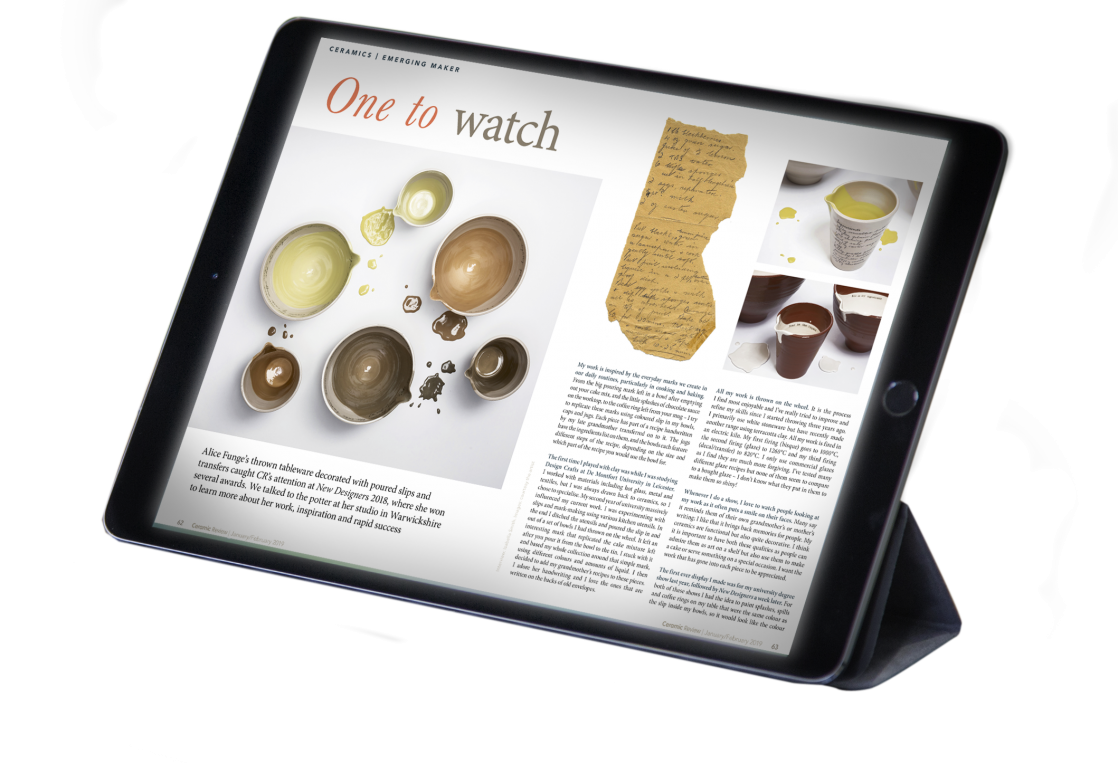

Welcome to Ceramic Review

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

Ceramic Review Issue 334

July/August 2025

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

July/August 2025

Toni De Jesus takes traditional forms and decoration and disrupts them into vivid, expressive pieces. Andre Hess uncovers the background to his ethos

In The Guardian of 16 December 2024, the designer and writer Adam Nathaniel Furman wrote: ‘This is sorcery level craft! I love ceramicist Toni De Jesus’ Fleabane Vase. I love how he references the importance of flowers in queer symbolism. The decorative, the floral, has always been a very strong thread in British queer visual culture, but rather than isolating us, it has tended to connect us to wider decorative traditions that are much loved. De Jesus’ vases are also just exquisitely crafted and beautiful, charting their own aesthetic sensibility, and I very much hope to own one myself one day.’

Columnists are famously poor at writing about ceramics but it is still worthwhile noting the idea of queer/camp in our encounter with De Jesus’ work. For example, earlier in 2022, he conceived Amor-Perfeito (Perfect Love) as a response to a porcelain plate from the Nantgarw China Works. The creation of Amor-Perfeito also marked a profoundly personal moment, as it provided him with the opportunity to come out to his father. His work, however, is about far more than this.

We live at a time where ceramics has a lively existence online. A glanceat De Jesus’ Instagram account attests to a shiny brightness, curatorial interest and of exhibition success. A kind of feverishness that has taken his work to Venice (Homo Faber, part of the 2024 Venice Biennale) and New York, and a large show moving from the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Madeira (MUDAS) to the UK.

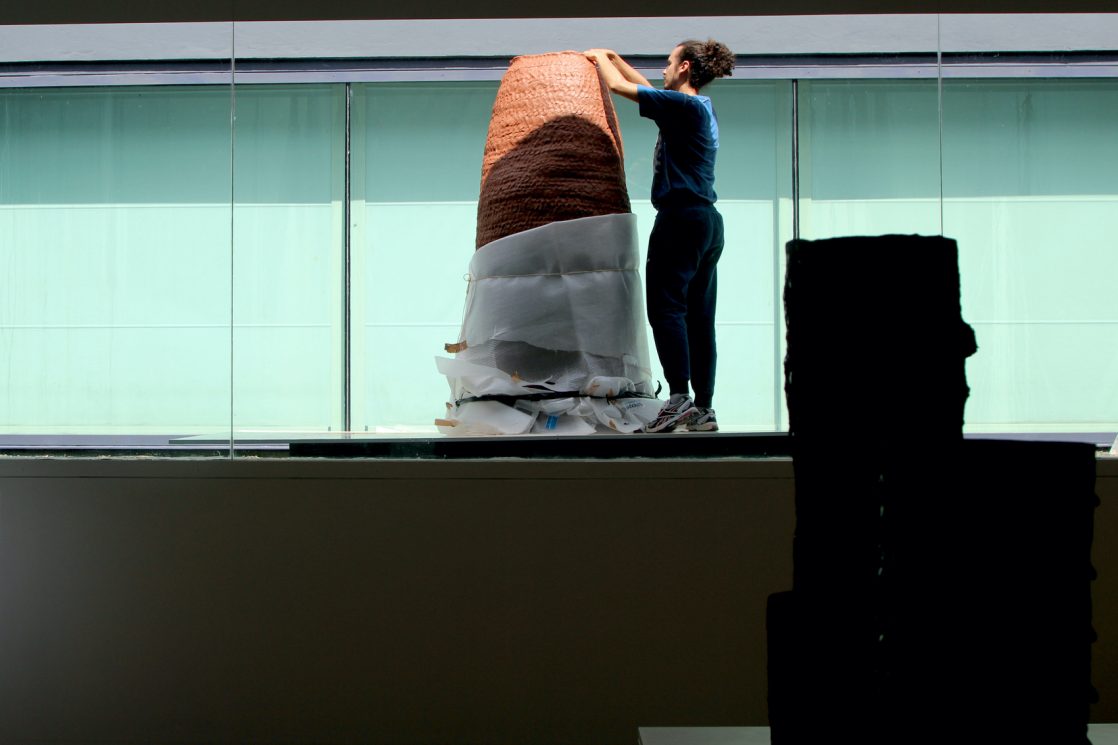

The Madeira exhibition, titled Cacúlo, which included a residency project that involved a giant coiled piece as well as other works, was on at the Llantarnam Grange until earlier this year and is touring to the Ruthin Craft Centre. In the last couple of years, De Jesus has shown with the J. Lohmann Gallery in New York and is now represented by them. He also completed residencies, not only at MUDAS but at the International Ceramic Research Center, Guldagergaard, in Denmark. There was also a feature in Vogue magazine in March 2024.

ARTISTIC VISION

De Jesus’ work takes on both classical and traditional shapes. Picture a small charity-shop teacup with floral decoration and gold lustre on the handle. Now take those two elements and transfer them onto larger more robust/expressive pieces. However, his work contains what can fairly be described as disruptions: these come in the form of vessels without bottoms, vessels with encrustations and ‘growths’, vessels so covered in applied flowers rendering them difficult to use, vessels with holes, vessels lying on their sides, distorted vessels, ‘unfinished’ vessels, vessels with a profusion of handles and fragments of vessels.

A unifying feature in his work is a visual and physical lightness, as well as surface decorations with floral prints transferred or flowers modelled and applied. The work sometimes announces itself unambiguously as a surface that is almost flying free of the shape or sitting in tension with it. But it is not decoration for decoration’s sake. There is always a point.

The persona De Jesus offers us is also a disruption in terms of the traditional potter found at ceramics fairs, in membership organisations and in many galleries. He is fine-boned, tentative in his movements and shy. We drag with us the sensibilities we grew up with and acquire later, and which we either reject or celebrate. We see all of this in his work. His style is never primarily the stuff of outrage, camp, queer, protest or campaign. The clay is everything.

When asked about his formative years, he answers: ‘I was born in the UK, with both parents from Madeira. The family moved back there when I was six and we stayed until I was 13. Despite being there for only a short time (I hasten to add that seven years is a long time in a child’s life), it was incredibly formative and holds strong memories.’

That is not surprising, because Madeira is vivid, bright and hyperbolic. The boy’s world would have been filled with decorative tiling, colourful patterned traditional costumes that would have been used for the many festivals, tablecloths of eyelet embroidery, colourful earthenware pottery and handmade lace. And then there is the Catholic church’s propensity for visual excess.

‘Having been born in the UK and now living in Wales (Cardiff) means that part of my identity resides here, despite feeling like not really belonging,’ he reveals. ‘I have found this conflict in me interesting. That, and finding a place between tradition and breaking that tradition, function and non-function, craft and art. This is where my visual vocabulary is formed.’ It is possible to state, taking Madeira into account, that the formal resemblance of his work to the aesthetics of camp and queer, as they are, is only incidental to it.

Glynn Vivian, July 2022

HOOKED BY CLAY

His first contact with clay was at school. When GCSE Ceramics became an option, De Jesus grabbed it and continued with it through A-levels. Alongside it came textiles as part of fine art. He remembers ‘incredibly encouraging’ tutors. After this came a Foundation course at Brighton and Hove, where he found himself ‘hooked’ by the clay and the people working there.

He was the first person in his family to go to university, but what he was planning on studying needed to be revealed to his family slowly and carefully. This was almost as big as ‘coming out’, and he had to start off by saying he was going to study art. This alone was a bitter blow, apparently, and he was obliged for financial reasons to take a gap year and a job. He worked all hours to save up the money. This included a studio assistant role with Anna Barlow, herself still an assistant at Kate Malone’s studio.

When the time came, De Jesus packed his bags and headed for the Cardiff School of Art and Design. His tutors were Duncan Ayscough, Natasha Mayo, Claire Curneen and for a short time Peter Castle before he retired. A key consideration in his creativity was the structure of the course. ‘Because it ran across the art and design school, it meant the course was cross-disciplinary and we had subjects with other students and tutors from other courses. This included Ingrid Murphy who taught on the Designer Maker course,’ he explains. It is possible that the disruption that characterises his work can be traced back to Cardiff.

Glynn Vivian, July 2022

After he graduated, the university offered him an ‘Enterprise Studio Space’, where he worked while learning the business of being an artist. Then, during the various coronavirus lockdowns, he found a small studio at the Fireworks Clay Studios and slowly thereafter upgraded to a larger space. ‘There is a massive group of us mainly working with clay here at Fireworks. I am extremely lucky to be part of this community. There is a body of knowledge that I am lucky to have access to,’ he reveals.

He works in terracotta and porcelain, often juxtaposing them, seeking the contrast he loves and the meanings it might evoke. He is not devoted to any means or technique. He often coils his work but enjoys using thrown and cast elements. Since Guldagergaard, he has become increasingly interested in fluxing and melting materials. He has built up a library of test tiles that end up neither ‘glaze’ nor ‘clay’ that have come out of a variety of materials, percentages and firing programmes. He says that his space is ‘in a constant state’, especially during making phases. He owns a small electric kiln and a test kiln.

FEELING OF BELONGING

De Jesus is suspicious of the word ‘influences’ when I raise it because it seeks a list of names and resemblances. In reality, the artist looks to things as research for ideas already present in their visual language. He looks widely and abundantly and far beyond ceramics. When forced to come up with some names, however, he mentions Gordon Baldwin, Alison Britton, Carol McNicoll, Jacqueline Poncelet, Angus Suttie, Bela Silva, Lourdes Castro, Cecile Johnson Soliz and Johannes Nagel. He says there are many more but would like to draw attention to Claire Curneen.

‘Subconsciously, I have been absorbed by her aesthetic,’ he says. ‘Although her work is figurative, we are both working with the vessel. I am moved especially by the tips of the fingers and the branches. They reach out and suggest something happening or merging.’ Being familiar with the Leach tradition and its rich history, however, also gives him a feeling of belonging.

His projects are not about ‘queering’ or making ‘camp’ of ceramics but about an authentic self-expression. It is about authoring and constructing a personal identity as a ceramicist and locating his work not inside only ceramics but in the wider world of made things. While in Brighton an old, over-decorated teacup called out to him and caused an explosion in his head. It is possible that that little cup was waiting there for him.

For more details visit tonidejesus.com; @tonidjesus; Cacúlo, Ruthin Craft Centre, 5 July–5 October; ruthincraftcentre.org.uk

Ceramic Review is the international magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

As a subscriber to the print magazine, you also get FREE access online to the entire Ceramic Review archive – going all the way back to our first issue in 1970. Digital subscriptions are online only.