Welcome to Ceramic Review

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

Ceramic Review Issue 327

May/June 2024

Ceramic Review is the magazine for contemporary and historical ceramics, ceramic art and pottery.

May/June 2024

Danish ceramic artist Bodil Manz is recognised for her light-enhancing, paper-thin cylinders. Now in her 80th year, Natalie Baerselman le Gros honours her career

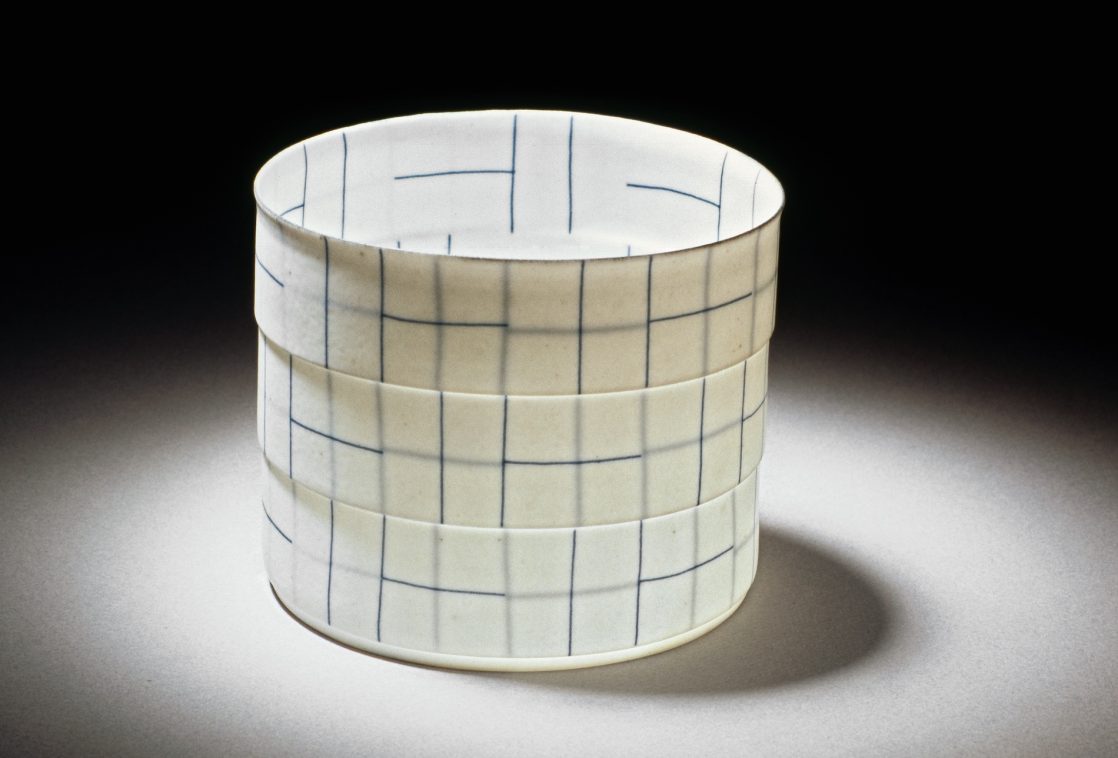

'Dessau', form with stepped wall, 2018, H16 x D12cm

Bodil Manz’s ceramic style is unmistakeable. Crisp white cylinders of the thinnest porcelain, glazed with primary plains and pin-perfect grids inside and out, animated by the ever-transforming fall of natural light. Her ability to bring variety and experimentation to so simple a form and so distinctive a visual image would forgive any assumptions that the cylinder was the be-all and end-all of her career. But her oeuvre takes many twists and turns, all celebrated in this, her 80th year.

EARLY YEARS

Manz’s experience with clay began early, both as a raw material and as a finished, functional object. The artist remembers her grandmother’s and mother’s collections of porcelain cups from Bing & Grøndahl and the Royal Porcelain Manufactory, Nordström ceramics and Saxbo works by Nathalie Krebs. Some of her earliest recollections are trips to her family’s smallholding in Bjergene, where coastal slopes bore blue clay that she would shape into small objects and set upon the rocks to dry.

She became increasingly interested in artistic pursuits as a child, showing little enthusiasm for academia. In her mid-teens her mother enrolled her in ceramics classes with the sculptor Møller-Petersen and it was here that Manz decided to make clay her life. She went on to work in the studio of Gutte Eriksen, where she was taught techniques in a Japanese manner (for Eriksen had spent many years in Japan and under the teaching of Bernard Leach). Manz recalls: ‘I sat at the potter’s wheel and turned one, two, three… one bowl after the other, and then she came and squashed the ones that had poor edges. She taught me a lot about edges.’

In 1961 Manz was accepted into the Danish School of Arts and Crafts in Copenhagen. Under the tutelage of ceramists such as Richard Kjaergaard, she learnt a fundamentalist approach to the medium. Students were encouraged to continue the timeless and functional tradition of Danish ceramics. An intention rooted in a connection to the raw material, one of the only raw materials found in Denmark, and the creation of objects for practical use, whether part of a small studio pottery endeavour or the vast industrial ceramics manufactories.

Bodil Manz in studio, photography Ole Haupt

Three Cylinders with Blue, Black and Japanese Red, porcelain, 2001

Manz spent the summer of her second year as a trainee in England, working in the studios of John Solly and eventually Michael Leach, where she learned to use a Leach kick wheel. Then, during the summer of her third year, she worked at the Gustavsberg Porcelain company in Sweden where she met her future husband and artistic partner, Richard Manz.

Upon graduating in 1965, the pair embarked on an international tour. They visited Mexico for six months, teaching at the School of Decorative Arts in Mexico City, then travelled to America, advised that the West Coast was the place to study ceramics. They were invited to be guest students at the University of California, Berkeley, working under Peter Voulkos for four months.

The couple recognised a different approach to ceramic practice than they had been taught in their respective educations. They learned that there was no such thing as timeless expression, everything is tied to its time, and that a ceramic career should embrace experimentation as any other artistic career might.

Voulkos encouraged the Manzs to discover themselves as ceramicists. Significantly, they also learned about studio porcelain practices, largely unheard of in Denmark as porcelain tended to be the territory of the industrial ceramic giants.

The pair returned to Denmark and set up their workshop in an old school in Starreklinte, in the rolling landscapes of Zealand, about an hour from Copenhagen. The site consists of numerous buildings, one of which they converted into their home, while another they made their studio. The ground floor houses their many kilns and a plaster workshop, dozens of plaster moulds of all sizes are neatly piled up around the room. Upstairs, large porthole windows frame the surrounding fields and spill light onto a neat, pitched gallery space where both the Manzs’ works are displayed in small groups that interact with the raking light.

'Rain', cylinder, porcelain. 2021, H17 x D15cm.

'Cross', cylinder with stepped walls, porcelain, 2004. H18.5 x D23cm.

SIGNATURE STYLE

Thanks to Richard’s technical skills, the couple began working with porcelain in a way unseen in studio pottery in Denmark, creating experimental sculpture works and architectural commissions, as well as continuing to make functional household wares of outstanding technical skill and beauty.

In 1982, Bodil was approached by Bing & Grøndahl to design a dinnerware service for industrial production. The result was Facet, finished in 1984. A white porcelain service decorated with a linear pattern of geometric shapes, hatching, and dots in subtle hues of blue, grey and yellow. The straight sides, clean edges and modest decoration is clearly identifiable as Manz’s signature style and is echoed throughout her career. It was while working on this series that she also discovered firing-transfers, a method that would be of great importance throughout her career and facilitate her application of colour and decoration in a strict, graphic manner.

A significant part of Manz’s practice is manifested through paper, whether as preparatory ‘sketches’ for her ceramic works or as explorations of paper in their own right. Her handmade papers offer the same rawness, variation in texture and potential for colour as clay and she often uses clay elements in their making: ash, sand, slips and oxides. In the 1997 Keramiske Veje (Ceramic Paths) exhibition in Copenhagen, Manz displayed 24 paper works entitled Hida alongside her ceramics. They took inspiration from the paper sliding doors and windows in Japanese houses, drawing on her interest in the fall and penetration of light through space and material that is important in her ceramic works.

However, it is her cylinders that Manz is most well-known for. The form became fully fledged in her oeuvre in the 1980s, but the idea was germinating in much of her functional wares long before. The familiar basic shape of the cylinder has enjoyed endless variation and beautification in the artist’s hands. Her proficiency at porcelain casting is manifest in works as thin as paper and as light as eggshells. This thinness exaggerates the translucent quality of porcelain to the near transparent, and the play of light and shadow between the interior and exterior is amplified with Manz’s decoration. She conceives the work as ‘an open sculpture in the round’.

Courtesy of the artist

'Winter Sunshine', cylindrical vessel, sand-cast porcelain, 1999. H26 x D34cm. Exhibited "Keramiska Veje", 2000, The Free Exhibition Hall, Copenhagen

Writings about Manz’s cylinders draw attention to visual connections to art history: the primary colour blocks of Mondrian and Malevich, the graphic geometry of Neoplasticism, the urbanity of Constructivism, and the clean lines of modern architecture. But Manz’s inspiration comes from within, from her own experiences and experimentations with the material and with the process.

She is preoccupied with a certain type of beauty: ‘I hope that when you see my work – even if it is something simple and white with a few lines – people will be a little bit surprised. If it can provide them with a new experience, if the light is on it, or if there are shadows on it, holes of light. People mustn’t be bored.’ Manz’s cylinders are variations on a simple theme, her command of which is poetry, a visually uncomplicated serenity that invites contemplation and quiet meditation.

TECHNICAL PROCESS

But it is in the comprehension of the artist’s technique that her cylinders can be truly appreciated. Manz’s process is one of extraordinary technical skill, intense delicacy and high risk. The artist begins with a plaster mould, made first from a positive clay impression of the intended final shape. A precise mixture of liquid clay, water and electrolyte is poured into the prepared mould and then poured out. The desired thickness of the final object determines how quickly the solution is removed, which, in order to achieve the extreme thinness of her works, happens immediately, leaving a thin slip-like layer on the interior of the mould. The plaster mould absorbs the remaining water and the porcelain hardens so it can be carefully removed from the mould and fired.

Bodil and Richard: 'Hojicha', 'The Apple Cup', porcelain, turned with slip decoration, 1976, H6.5 x D8.5cm

Studio Picture, 2008

After bisque-firing to 900°C, Manz applies a flat matte white glaze to the interior and exterior and fires again to 1300°C. Her decorative phase is created with three-dimensional paper models before being cut out from coloured foils and applied with water. A third firing, again to 1300°C, seals the colours into the glaze, while designs that feature any red elements are applied after this and fired again at a lower temperature.

For a significant portion of her career, Manz’s practice was partly collaborative, her studio activity bound up in the shared space and technical knowledge of her partner Richard, but his death in 1999 at the age of 76 presented not only a personal trial but also an artistic challenge. Manz recalls: ‘Many ceramists held their breath and wondered how I would get on without Richard…but I have learnt. I felt I must honour him by showing I can manage.’

The immediate results were a group of large sand-cast cylinders, larger than she had ever produced before, and decorated, not in Manz’s recognisable graphic style, but with expressionistic gestural sweeps of colour, drippy glazed edges and scored surface texture. She began to work more with sand-casting to produce experimental sculptural works as well as plaster and porcelain plaques that responded more intensely to her natural environment: the bark on trees, sandy coastlines and undulating fields. This process liberates Manz from the restrictions and risks of the plaster-moulding process, allowing greater variation in the scale and purpose of her works.

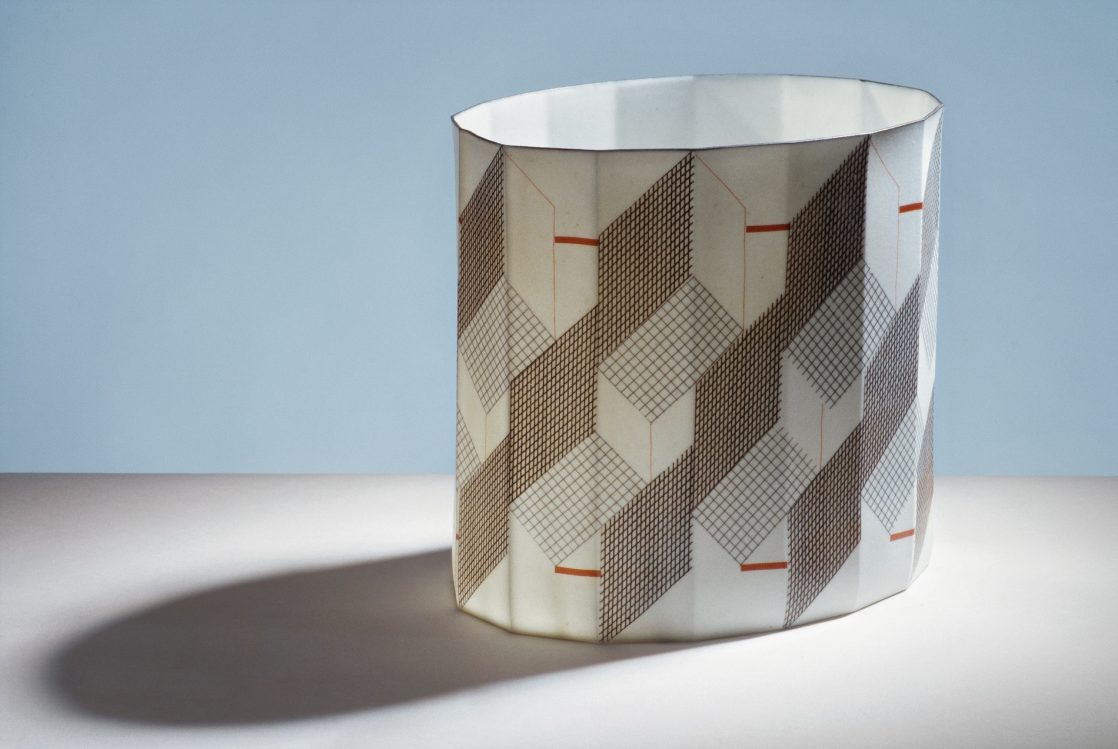

Today, Manz continues to explore the possibilities of the cylinder, both in form and decoration. Her visual language in this vernacular has developed into stepped cylinders, oval and 16-sided containers, she has perforated the cylinder walls to give light greater passage through the porcelain, she has worked in series by grouping many cylinders as a single work. She has collaborated with her children, an architect and a designer, to create new graphic decoration or structures around the cylinder.

Courtesy of the artist

Sixteen-sided oval form, porcelain, 1997, H16.5 x D22 x W17cm

In an exhibition in 1972 at Den Permanente (The Permanent Exhibition of Danish Arts and Crafts and Industrial Design) entitled On Being a Ceramist, the Manz’s declared: ‘Producing ceramics is a constant work process. This process cannot be ended, as it is not just one’s work but a hobby at the same time, leading to ever-increasing curiosity and excitement…focussing and concentrating on a single object such as a sphere, a square, a cylinder, a cup, fundamentally something quite ordinary, the stuff of everyday life, indeed almost banal. We discovered fresh aspects, and suddenly “the ordinary” became a new experience.’

It is clear that this statement, some 50 years later, still rings true for Manz, as she continues to find new avenues of extraordinary in the ordinary.

For more details visit bodilmanz.com. Bodil Manz will be showing a collection of new works at Gallery Weinberger-Shandoff, Copenhagen, 21 March–14 June 2024

Images: courtesy of the artist; Ole Haupt; Erik Brahl

Courtesy of the artist